Our Chief Executive, Tom Chance, takes a look at new academic research, commissioned by the Government, on community led housing and loneliness.

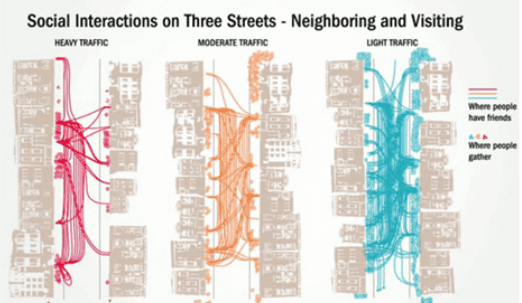

I first came across one of our Trustees, Nicholas, speaking about this famous study of neighbourliness and traffic in San Francisco:

The researchers found, in 1972, that people on low traffic streets knew twice as many neighbours and had three times as many friends as those on high traffic streets.

Create Streets, Nicholas’ outfit, argues that simple design choices have a huge impact on our wellbeing. Another example that stuck in my mind was front gardens. Not having one, stepping straight into the street, isn’t nice and gives you no reason to linger and chat to neighbours. But having a really long front garden also separates you from passers by and neighbours, and means you’re more likely to jump into your car and drive off without seeing anyone.

The LSE research nods to this literature on physical design, but wanted to look at community led housing and asked if there’s anything special about it in relation to loneliness.

They looked at five community led housing projects, including Bristol CLT’s homes at Fishponds Road. They looked at how each of these projects affected three types of loneliness: social loneliness arising from social isolation or a deficit of social connections; emotional loneliness from a perceived absence of meaningful relationships or sense of ‘belonging’; and existential loneliness where a person feels completely separate and isolated from others.

In the community led housing world there’s a perception that this is mainly an agenda for cohousing, which is all about intentionally creating closer communities.

But actually the research found that in all cases, community led housing was reducing all three types of loneliness.

The idea that physical design can reduce loneliness is pretty well accepted, if rarely reflected in the boxes that volume housebuilders throw up.

But this new research commissioned by the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) finds that there are two other factors that can have a big impact on loneliness:

Joint activities

Shared space

Physical design

All CLTs reduce loneliness for those people involved in the process – in the joint activities of meeting, designing homes, organising community consultations, and so on. The more the CLT works to recruit and involve members, the more it reduces loneliness in its local community. The more meaningful the interactions, the more they give people a sense of power over their lives and their local area, the better.

Our new CLT Essentials Handbook has a chapter on member and community engagement to help you do just this.

Bristol CLT didn’t just create a community of volunteers through the long process of designing the project. They also created a community of residents. The shared owners and tenants were trained to finish off the fixtures and fittings in their homes, and helped to create their own community garden – joint activities around shared spaces that were physically designed at the centre of the new homes.

This participation is part of what makes CLTs special.

CLTs aren’t just about a few local do-gooders forming a non-profit to provide homes for others on low incomes.

CLTs are about communities coming together to gain power and capability through the ownership of their land, homes and other assets.

For Julius Kimburgh Jnr, speaking at our AGM about Crescent City CLT in New Orleans, CLTs are about redressing multi-generational racial inequality. In a recent article he defines stewardship as “intentional efforts to empower residents with information and tools to grow intergenerational wealth through higher incomes, asset appreciation, and entrepreneurship.”

CLTs can have a profound effect on communities that goes far beyond providing some additional homes.

This LSE study shows that the relationships we foster through being involved with a CLT, and the control it gives participants over their lives and the changes affecting their local area, go a long way towards reducing loneliness. The research is well worth reading, to make us all think about how the way we run our CLT and the way we design our projects can do more.

The question for the Government, having commissioned this research, is: will they take note and implement the recommendations, including renewing the Community Housing Fund?