Our chief executive, Tom Chance, recently went on a study tour in the USA organised by the Local Trust. He writes about what he learned from over the pond…

After some soul searching about flying (for climate reasons I last flew long-haul in 2006) I joined a delegation led by Local Trust to study community-led initiatives and place-based regeneration in the USA.

In a packed week we were whisked around Boston, Lowell MA, Chicago and Washington DC. The question was – what could we learn, and should there be more transatlantic exchange?

I particularly enjoyed the company of my fellow delegates – leaders from UK government, think tanks, business and civil society from whom I learned as much as I did from the places and people we visited. I’d never normally spend a week with a group like that. What a treat!

This is a brief account of some of my reflections from the visits.

The good – collective leadership

In such a decentralised country, it was noticeable how enterprising and collaborative the civic leadership was.

People we met felt they had permission (or didn’t need it) to be creative and ambitious, and recognised the value of building partnerships.

In Lowell we talked to the city mayor and manager, the university chancellor, the local development and finance corporation, an urban national park, a community-run makerspace and a local arts studio facility. They all shared a vision of how to revive their ex-industrial town, and they valued the contribution that they each made to bringing that vision about.

The Boston Fed – the regional branch of the Federal Reserve – goes far beyond tinkering with monetary policy. They used their status to convene partnerships of local government, businesses, community organisations and banks to pitch for funding for local economic development. The focus is on people on low incomes and communities of colour. They’ve channelled over $28m into these places, funding small business loans and training, providing wraparound support, and identifying changes to state policies in areas like benefits and transport. It’s hard to imagine the Bank of England doing this!

I was delighted to visit Dudley Street, home to a Community Land Trust and community organising body that work hand-in-hand to develop this deprived area of Boston without displacement. They own over 30 acres of land which they lease to co-ops and homeowners with over 200 homes, a community allotment, a large urban greenhouse farm and various shops and businesses. A senior representative from the city government talked about the productive partnership they have, and the importance of the growing network of CLTs across the greater Boston area.

It reminded me of the growing confidence of the CLTs and city government in the Liverpool city region – a shared vision of community ownership of land helping to direct investment towards building community wealth, as an antidote to gentrification leading to displacement.

A really striking kind of collective leadership emerged in Chicago through a process to develop quality of life plans. A national body dedicated to local leadership gave funding to neighbourhood organisations, which paid for a community organiser to bring all the key local stakeholders together to make a joint plan to improve their quality of life in the area. It might cover anything from education to housing, safer streets to jobs. This built the capacity and shared vision at the local level to attract and direct investment – private sector, philanthropic, and public money.

One of these plans was the basis for a neighbourhood regeneration project led by a sort of housing association. They employed another community organiser to lead the local engagement. She was able to patiently piece together a collective vision for the scheme, rooted in the local community. Funding from the national agency (like Homes England) was flexible and patient, supporting a project that rebuilt housing – yes – but also brought a new grocery store to the area and invested in community groups.

That sort of holistic, flexible funding is sorely lacking in the UK where public and philanthropic funding is severely siloed.

The bad – disinvestment and displacement

For all the positive partnership working, civic leaders in Boston, Lowell and Chicago were struggling to tackle unbelievable levels of disinvestment and displacement.

There is also such a strong racial justice theme to these problems in the USA. It figured far more prominently in the thinking of those we heard from, and indeed many of those leading figures were people of colour with direct personal experience of the problems. Quite unlike the UK.

In Boston, the universities and private sector have displaced communities to such a degree that one university representative talked of their community work as ‘reparations’. The challenges in Lowell were more reminiscent of those in Oldham, Walsall or Merthyr Tydfil.

But Chicago was like nowhere I’ve been in the UK, and perhaps across Europe. As you drive south out of the high-rise, super-wealthy downtown you suddenly hit the south side – two-storey buildings half-empty, litter-strewn vacant lots, almost no businesses or high streets. Decades of overtly racist policies have sucked wealth out of the predominantly black neighbourhoods – such as ‘red-lining’ an area within which nobody is allowed a mortgage, only a rip-off contract with weak rights and high costs. The population has collapsed and nobody seems to have invested at a scale required to turn the area around.

It was like East/West Germany in the 1990s, but at a city scale.

Communities were also struggling to gain a voice, and access capital. A wonderful community-led project in Bronzeville, south Chicago, waited 15 years for capital investment. They, and other community organisations, were organising to influence political processes but didn’t seem to be any more present than they would be in the UK. A private developer presented an ambitious regeneration project called the 78 which was glitzy and impressive, but lacked any involvement from nearby communities and any sense of the meaning of ‘community’ beyond people who live in homes or frequent cafes and shops. I don’t want to turn my back on the 78. I want to marry that access to private capital with organisations like those in Bronzeville…

We met the deputy mayor for economic development and the housing commissioner in Chicago. They talked a good game, and seemed driven by a genuine passion to right historical wrongs and get more investment into the ‘black and brown’ communities.

It was similar in Boston and Lowell – some communities were organising to gain a seat at the table, but they weren’t recognised as being on a par with local government and business, much as in the UK.

The beautiful – the activists

We met some wonderful, beautiful people. They glowed with optimism and activism. Academics, financiers, government officials, tour guides, politicians, business people, community leaders. Oh, and a few random locals in bars.

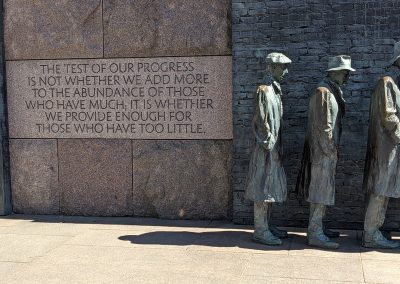

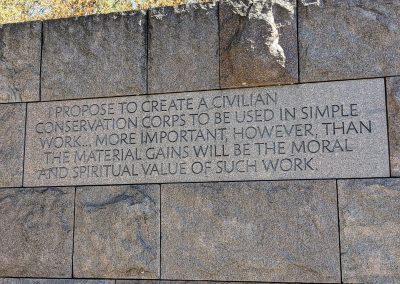

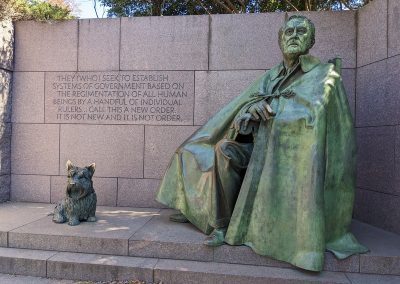

I was thinking of them all when walking around the astounding Franklin Delano Roosevelt memorial in Washington DC. That ambition to provide enough to those with too little, to value the moral and spiritual aspect of a ‘civilian corps’, to seek to build this rather than a regimented top-down system masked as ‘paternalism’.

One of the last groups we visited was Inner-City Muslim Action Network (IMAN). Rooted in the Chicago community organising traditions of Saul Alinsky and the black panthers, they were organising for social and political change, and running wonderful arts, health, food and community facilities. Their executive director, Dr. Rami Nashashibi, wowed us all with his eloquence, depth of learning and inspirational leadership.

I was so pleased to meet John Smith, executive director of Dudley Street, and his team. What a warm welcome they showed us, and what enthusiasm and love they bring to their community.

I also really took to the chap who showed us around Lowell Makes – it’s a feat to see volunteers run such a complicated space full of dangerous and expensive equipment, and to support so many hobbyists and small businesses… doing it all for the love of it.

In Chicago, a philanthropic trust funds grassroots ‘changemakers’ in recognition of this. Core funding is always the hardest to find – you can raise millions to develop some homes, but it’s fiendishly difficult to to fund the salary of somebody to start organising the community around it in the early stages. We need more funders like the Chicago Community Trust.

There has been a lot of talk about beauty in the UK development world in recent years. What they showed – and what I find in every Community Land Trust I meet – is that there is also beauty in the people, and latent capacity that can be brought to bear if you recognise and value it.

Coda

So what did I learn, in a nutshell? That the recipe for success includes strong collective leadership bringing the private, public and community world together around a place; building collective capacity, especially among community activists who are usually overlooked; and pursuing a shared vision with a can-do attitude.

But how do you take this from interesting examples to the mainstream, at scale?

At the end of the visit I met Tony Pickett, my counterpart in the US, for breakfast.

Like us, his organisation is grappling with the scale question, and starting with a recognition that it won’t happen by trying to replicate the stories of Dudley Street and other pioneers. No, instead, we are seeking to draw strands of inspiration to develop more replicable models that are better able to access capital, partner with public and private institutions, and expand quickly.

One approach they’re taking sounded like something we’ve discussed, but not yet tried, in the UK. That is, for the national body to establish a new CLT in an area at risk of gentrification; for the national body to raise a fund to go out and buy land and develop properties; and over time, as the membership and governance is established, transfer ownership to the local organisation. Top down meets bottom up.

Another approach is directly inspired by our work in the UK. After years of operating a national list of consultants, they are starting to develop a network of regional support organisations not unlike our enable hubs. They see this will give them a better chance of developing the supportive ecosystems of partnerships to grow at scale.

There’s a jokey Thai phrase which translates as ‘same same but different’. The idea is that two things might be somewhat different, but at the same time sufficiently similar to not get too hung up on the differences.

That’s how I felt, rounding off my trip. There’s so much to learn from the differences, whether the racial politics or local government powers.

But really we – in the US and the UK – are facing the same sorts of challenges, and coming at them with the same sorts of strategies. And so understanding those different strategies is of huge value to us in the UK.