Our chief executive, Tom Chance, recently attended the International Social Housing Festival in Barcelona to launch the new European CLT Network. He writes about one theme he picked up in his time there…

International conferences are great fun. But I do wonder about the value of attending them and of participating in international networks like the brand new European CLT Network.

I love the idea of sharing across borders, and enjoy the conversations, but just how useful is it? Can we transfer any of the ideas from countries with very different cultures, markets, industries, policies?

In Barcelona, among many interesting ideas, one theme made a very strong impression on me: the role of intermediaries in achieving scale.

In the UK we tend to assume that everything must come from the bottom up, and that any support – funding, policies, expertise – should be connected directly to groups on the ground. After all, it’s the wisdom of communities that we wish to get behind!

So we assume that CLTs are started by communities and everything is very DIY – they buy land, build homes and then manage them, solving problems along the way.

This leads to a particular approach to policy. For example, councils decide to put out sites for community-led housing. The sites are usually small and the council has already determined they’re too hard to develop themselves. The councils invite groups to bid, which requires a significant amount of technical skill, time and expertise. The bids are competitive, so communities try to plead their sob stories to win. If they succeed they are then left to raise the money and find the expertise to get a planning consent and then build them out and manage them. The result is a very slow, expensive process prone to failure.

Often councils take from this experience that community led development is inherently slow, time-consuming and prone to failure. But it isn’t, it’s just the process communities have been forced to follow that suffers these faults.

Hearing about Barcelona was quite a contrast.

In Barcelona they have formed what they call a ‘col·laboració publica-social-comunitaria’ – a ‘public-social-community’ collaboration to try and build or rehabilitate 1,000 flats over the next few years.

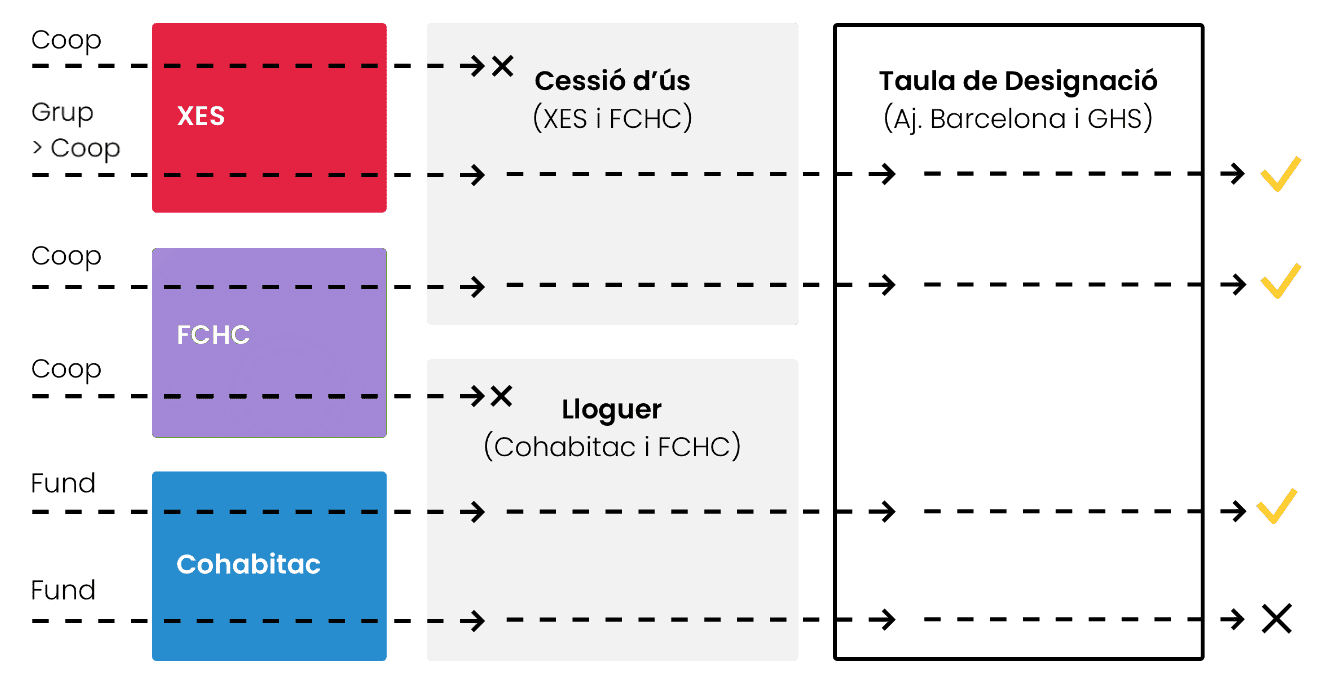

The city council provides good-quality sites (or empty homes), and then two different partnerships take them forward. One of these is a partnership between solidarity economy network (XES) and housing co-op federation (FCHC) who develop half the sites with a kind of cohousing. Another partnership is between a sort of housing association coordinator (Cohabitac) and FCHC, who develop the other half for social rent. Each partnership puts forward a proposal for each site, working with their networks to develop proposals, and a board set up by the city council approves or rejects them. The existing co-operative housing developers then design and build them out, sometimes with the future occupants as cocreators. You can read more about the process here (or with a Google translation).

They are now looking to adapt this process to create a Community Land Trust to take on stewardship of the land. The same networks are exploring what sort of CLT model or models might work across the wider Catalonia region.

Key to the success of this model is the existence of intermediaries – the federations and partnerships, the regional housing developers and co-operative finance bodies. These intermediaries do a lot of the heavy lifting, and provide a lot of the initiative. So the members of the individual co-ops and cohousing communities are taken along for the ride, and given input and control where it matters to them.

These arrangements are underpinned by public policy instruments including a loan guarantee for the early risky stages of projects, and a light-touch form of registration for new housing providers.

While community groups and co-ops in cities like London, Bristol, Manchester and Leeds have struggled to overcome the many obstacles left in their way, in Barcelona they are carried along by intermediaries that are building 1,000 community led homes.

We have our own success stories in the UK – cases where we have found a more scalable balance between bottom-up energy and more top-down capability.

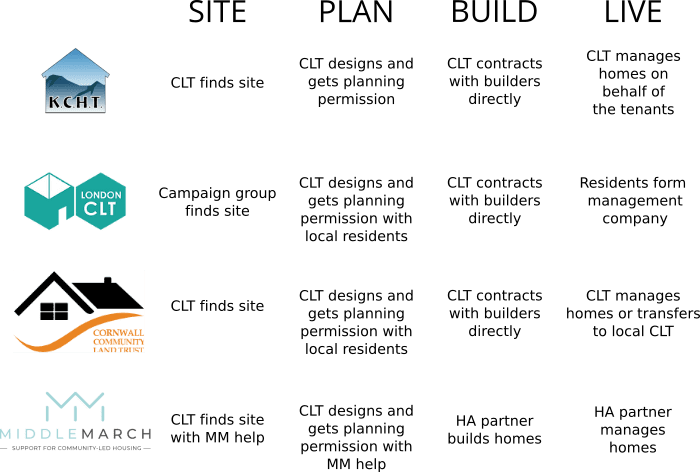

Here are four approaches taken by CLTs that create potential for a bit more scale by building capacity across multiple projects. Each is a simplification to make it clearer, and each of the first three CLTs have also pursued other approaches alongside these:

- Keswick Community Housing Trust, which has taken the DIY route but developed multiple projects, all held in one democratic membership-based for the town, rather than having to create a new group, expertise etc for each project.

- London CLT, which picks up sites secured off councils by a local campaign group under its partner Citizens UK, codesigns the scheme with people local to the sites, builds them, and then helps the first leaseholder occupants set up a Resident Management Company for each scheme.

- Cornwall CLT, which finds sites across the county, codesigns the schemes with local people, builds the homes and then either transfers them to a local CLT or holds them centrally when communities are too small to want the responsibility.

- Middlemarch CLH, which helps CLTs to identify and secure sites, gain planning permission, and find a housing association partner to build and manage the homes on their behalf.

This diagram illustrates the different arrangements and roles they use at each project stage:

There are many more examples like theirs, in the UK and internationally.

Cornwall CLT and Middlemarch CLH are examples of the principal type of intermediary we have focused on: the enabler hub. They emerged from antecedents like umbrella CLTs and secondary housing co-operatives, and are a regional model of providing support to communities while also building an ecosystem of engagement from local government and industry. We have been at the forefront of raising over £4.5m of investment to go into enabler hubs, with mixed success.

So we have some of the building blocks to follow the Barcelona example.

For example, councils disposing of sites could work collaboratively with the local CLH sector and industry partners to create a framework approach. Map out a route through planning, finance, community skills and enabling, and ensure the right intermediaries are in place (or help create them) to act at scale across the sites. Vest all of the land in one or more CLTs, and assemble one or two developer partnerships to build out all of the sites, cocreating them with different co-ops and cohousing communities, which in turn lease the land from the CLT(s). In a city like Bristol, Liverpool or Manchester it might shave off some of the innovation and energy compared to the DIY approach, but it would be much more likely to deliver.

Intermediaries can come in many forms, and can be combined together with CLH approaches in different ways. We, ourselves, are a national intermediary, and groups like Oxfordshire CLT have tied together our support for the CLT part of their project with the support of the Confederation of Co-operative Housing to establish a tenant co-op that will lease the homes the CLT builds and owns. This is a picture of a networked ecosystem, rather than organisations jostling to do it all.

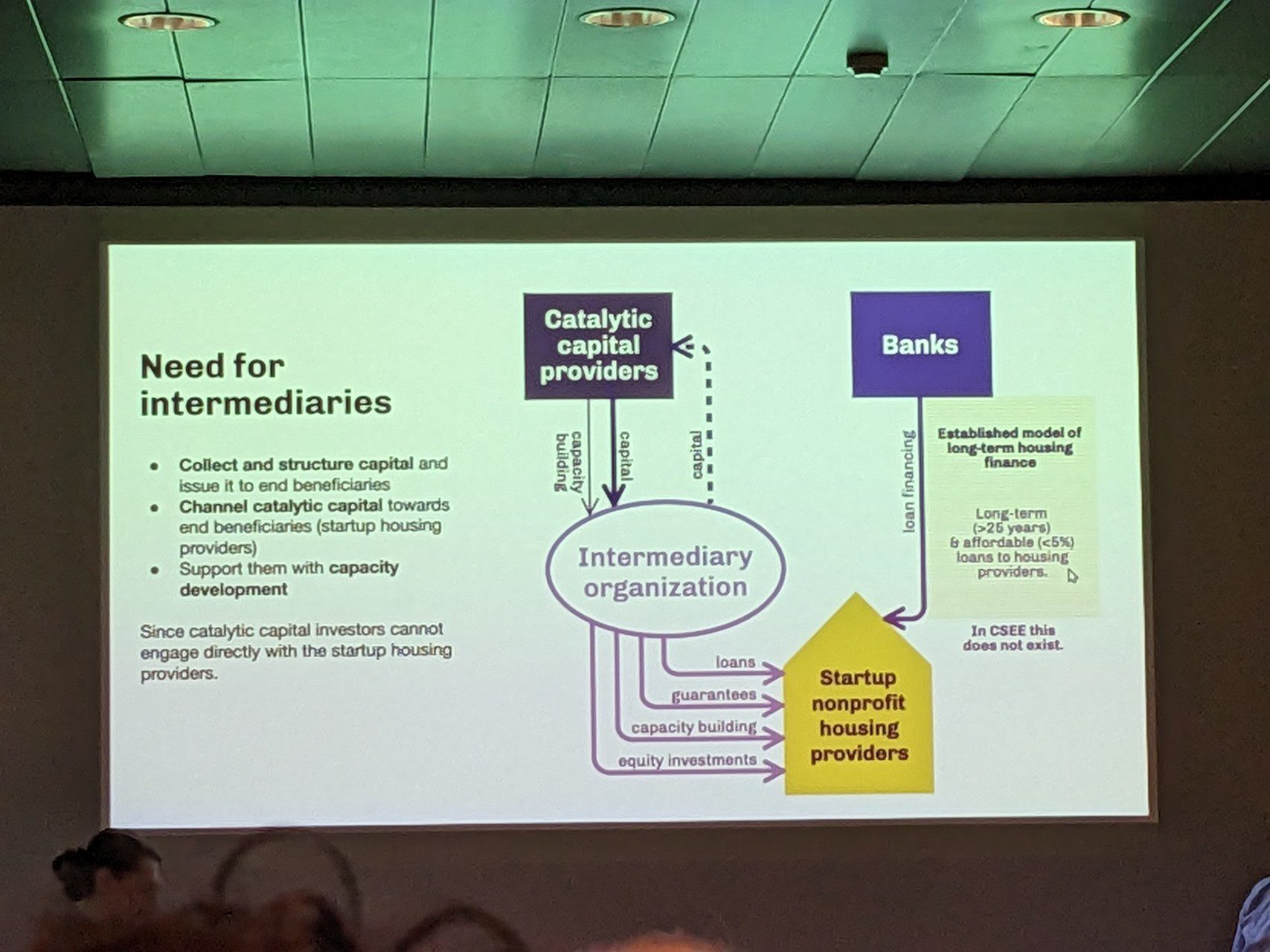

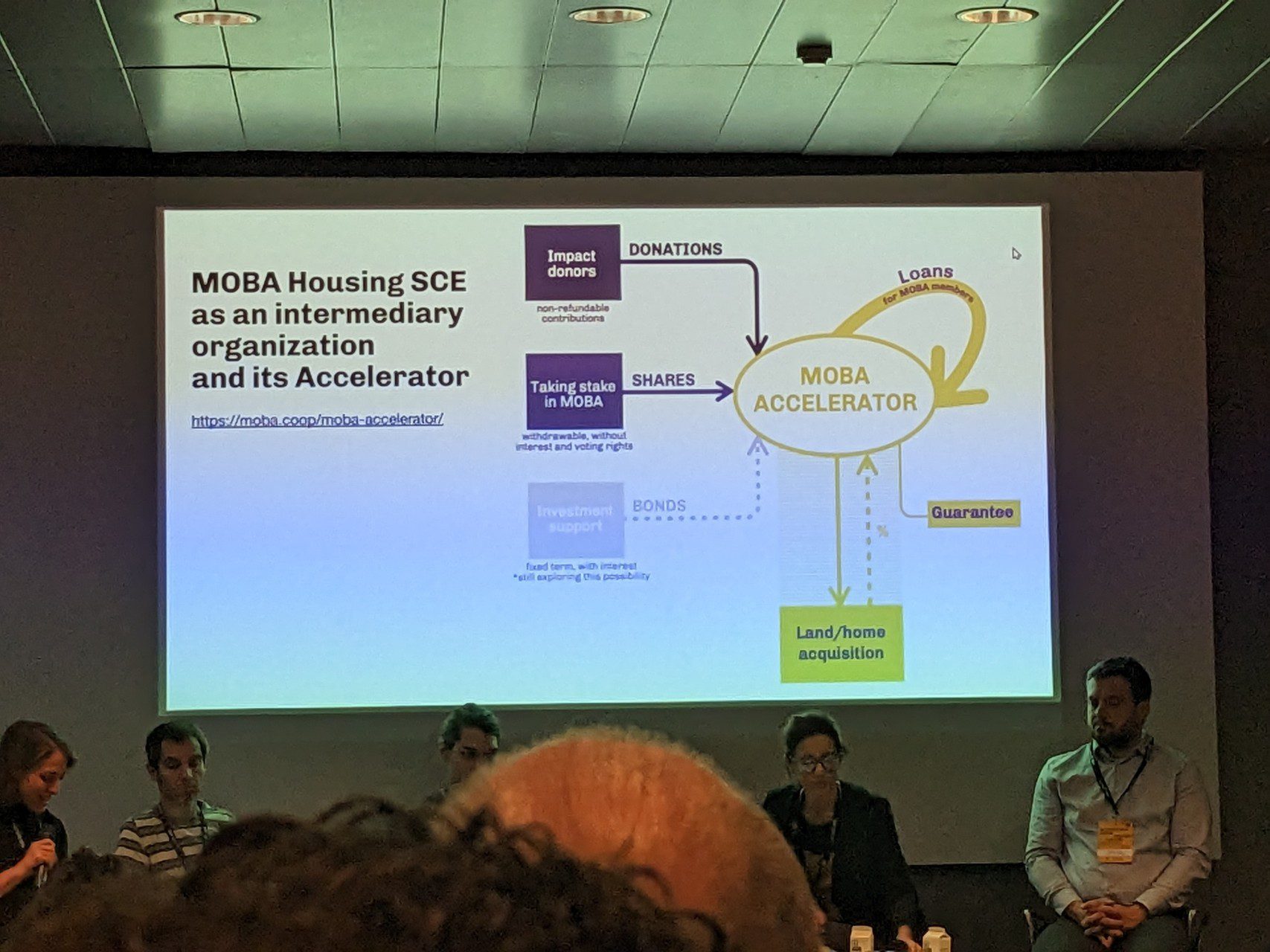

At the conference I also attended a workshop to hear about the approach being taken to intermediaries in south eastern Europe:

These two presentation slides show an integrated approach to creating financial intermediaries that can raise finance from a range of sources and channel it into community led housing projects. They aren’t raising money to invest in individual co-ops or CLTs, they invest into non-profit developers – another type of intermediary – that are able to acquire the land, develop the homes and thenhand them over to the communities.

We have plenty of intermediaries in the UK – here are a selection:

But somehow this has not added up to a real growth strategy for our sector. It is not achieving scale. There are frustrating disconnects – groups complain about a lack of risk capital, while social investment intermediaries struggle to find projects to invest in. Enabler hubs have been closing as star-up grants ran out prematurely, and struggle to cover their costs from the investment provided by financial intermediaries and industry partners.

Unlike the examples in Barcelona and in south east Europe, our intermediaries all focus on the group. So the investment intermediary raises money, but tries to invest it in groups; the enablers provide expertise to groups and expect them to raise the finance to pay for it; developers serve a group, and again look to them to raise some or all of the finance.

By contrast, those continental examples create partnerships across intermediaries – the finance intermediary invests in an enabler or developer that then builds out multiple projects, with the groups under their wing. They solve the key problems collectively, at a higher level, with greater economies of scale. The ecosystem of intermediaries come to communities with most of the problems solved. Community groups aren’t asked to secure land, raise finance or become experts in development; they are asked to provide the expertise they do have – the needs of the community, the local context, the design of the projects, the way they will live – and to then manage, steward and in some cases own the homes.

What I liked about Barcelona, and some other examples I heard of across continental Europe, was this joined-up approach to the intermediary layer. The creation of an effective ecosystem of intermediaries, able to overcome the familiar challenges around land, planning, finance, expertise, community capacity and to then provide a really strong offer to the communities who – after all – basically just want to exercise some people power in the way their homes are built, owned and managed.

We’ve some way to go, yet, in the UK, and plenty to learn from the rest of Europe. It will look different in our broken housing market, our policy contexts in England, Wales and Scotland. But perhaps it needs to have a much greater emphasis on intermediaries?